Forecasters expect a recession this year in major economies and a rebound in economic activity in 2021. This column asks how credible such forecasts of recovery are. The past record is not inspiring: forecasters have had little ability to tell in advance whether a recession will end in a rebound or continue on for another year. Policy choices, particularly on fiscal stimulus, are better guided by worse-case scenarios than by the baseline forecasts of recovery.

When the first Vox eBook on the COVID-19 pandemic was released on 6 March (Baldwin and di Mauro 2020a), hopes that the economic damage would be fairly short-lived were starting to fade: “While a short-and-sharp crisis is still possible, it’s looking less like the most likely outcome,” the editors noted. Since then, hopes have faded further. Leading economic forecasters predict deep recessions this year in almost all major countries.

What about 2021? Forecasters are counting on a V-shaped cycle and predicting recoveries for next year. For the US, for instance, the IMF forecasts that real GDP will decline about 6% this year but will bounce back by nearly 5% next year. Private sector forecasters agree: Consensus Forecasts indicate that V-shaped recoveries are expected in major advanced and emerging market economies, though in some cases the expected recoveries are somewhat tepid compared to the declines this year.

How credible are such forecasts of recovery? To shed light on this question, we look at how well Consensus Forecasts have done in the years following the onset of a recession over the last 30 years (1990 to 2019) for a large group of countries. We begin by identifying every instance since 1990 when a country was in recession, which we define simply as a year in which real GDP declined. There have been 151 recession episodes over this period in the countries that we study. Just over 70% of recessions have lasted one year. Most of the remaining 30% have lasted two years. Very few have gone on for more than two years.

Results

For all essential purposes, therefore, the main questions of interest are: once a recession starts, what do forecasters have to say about what will transpire in the following year – recovery or continued recession – and how accurate have such predictions been? Our findings are as follows:

Calling for a V-shaped recovery (decline this year, increase next year) is by far the most common strategy used. As the vast majority of recessions have indeed been V-shaped, this generally turns out to be sensible strategy. In 90% of such cases, Consensus Forecasts has correctly predicted a recovery in the year after a recession has begun. In other words, incorrect calls that a recession will continue into a second year are rare.

What about the cases when recessions have continued into the second year and sometimes even longer? These cases have proved challenging for forecasters. In 90% of such cases, the forecasts the year before have been for a recovery, and hence turn out to be incorrect. Surprisingly, forecasters are fairly slow to let go of the belief that recovery will arrive, so that even as the second year of recession is drawing to a close, in 20% of the cases forecasters are still predicting recovery that year.

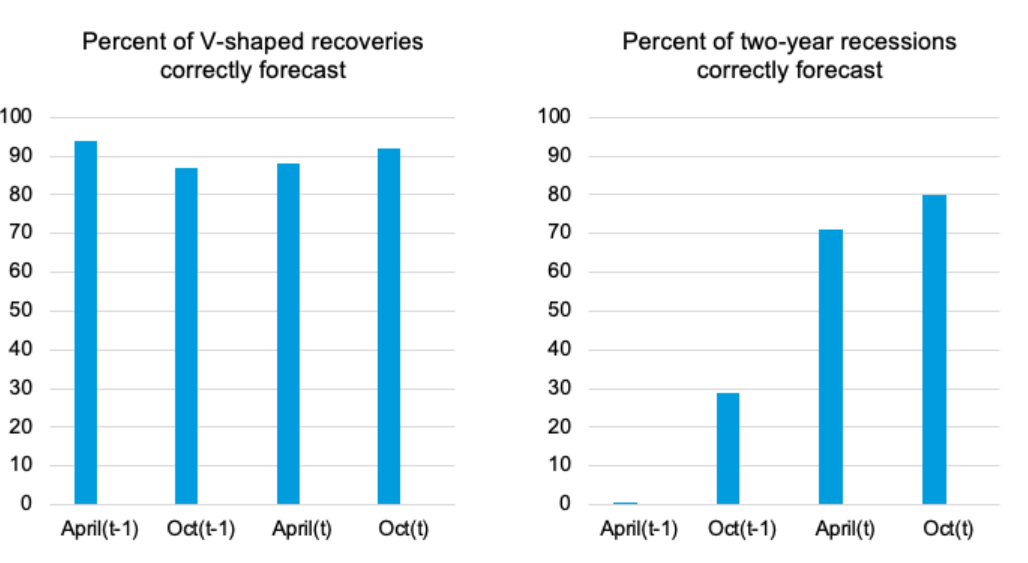

Figure 1 illustrates our findings, showing the performance of forecasts at four points in time, April(t-1), Oct(t-1), April(t) and Oct(t). The first two are year-ahead forecasts, made in April and October in the year in which the recession has started but what will transpire in the following year is quite uncertain; the other two are current-year forecasts, made as forecasters are becoming better informed about the course of events.

Figure 1 Predicted recoveries versus reality

The left panel of Figure 1 shows the good performance of forecasters when recessions turn out to be V-shaped: the percentage of recoveries called correctly in such cases is nearly 90% for both year-ahead and current-year forecasts.

The right panel shows the poor performance when recessions drag on for a second year. A year ahead, in April, forecasters have incorrectly predicted a recovery in virtually every single one of these cases. In the year-ahead forecast made in October, they flip their forecasts from recovery to recession in 30% of the cases. By April of the current year, the recognition of a continued recession is made in 70% of cases and this increases further to 80% by October. Put differently, even as the year is ending, in 20% of cases forecasters are still hoping for a recovery that will not arrive.

To summarise, forecasters have almost always called for a V-shaped recovery (recession one year, recovery the next). Since V-shaped recoveries have occurred 70% of the time, they generally end up being right. In the other 30 percent of cases, they only learn fairly gradually over time that the economy is departing from the standard V-shaped recovery.

Policy implications

As of April 2020, forecasters are predicting recoveries in most major economies in 2021. If past forecasting performance is any guide, it would only by October 2021 or so that forecasters would be reasonably confident whether 2021 is going to end up as a year of recovery or continued recession. Of course, this time could be different – forecast performance could be better than the historical record might indicate.

Nevertheless, given the past record, it would be prudent for countries to make policy choices keeping in mind the possibility of continued recession rather than anchor policies to the current baseline forecasts of recovery. The experience of the not-so-Great Recovery following the Great Recession of 2008-09 offers a cautionary tale. In 2010, baseline forecasts of robust recovery led to a turnaround in the fiscal stance in many advanced economies, a policy decision that in the opinion of many observers was premature (De Grauwe and Ji 2013, IEO 2014). The recovery turned out to be tepid – and the move to a tighter fiscal stance might itself have been one of the contributing factors to this outcome (Kose et al. 2013, Krugman 2013).

To conclude, during times of abnormal uncertainty, policy choices could be guided more by a risk-management approach instead of linked tightly to what would be appropriate under the baseline scenario. This is particularly the case for fiscal policy. At the moment, as Baldwin and di Mauro (2020b) note, there is strong agreement that “the case for decisive and coordinated fiscal stimulus is overwhelming”. However, concerns about debt sustainability are likely to create a strong constituency for a quick withdrawal of fiscal support even before countries are sure that a recovery has firmly taken hold.

Note: The views expressed in this column should not be ascribed to the institutions with which the authors are affiliated. The column build on work conducted when the authors were in the IMF’s Research Department and is not part of an ongoing evaluation by the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office.

References

An, Z and P Loungani (2020), “How well do economists forecast recoveries,” Working Paper, 20 April.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds) (2020a), Economics in the time of COVID-19, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds) (2020b), Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: act Fast and do whatever it takes, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

De Grauwe, P and Y Ji (2013), “Panic-driven austerity in the eurozone and its implications”, VoxEU.org, 21 February.

Independent Evaluation Office (2014), “IMF response to the economic and financial crisis”, International Monetary Fund.

Kose, A, P Loungani and M Terrones (2013), “Why is this global recovery different,” VoxEU.org, 18 April.

Krugman, P (2013), “How the case for austerity has crumbled,” New York Review of Books, June 6

相关新闻

-

应用经济学院师生赴通州大运河开展实践研学

2025/12/11

-

中国人民大学应用经济学院和西藏大学经济与管理学院开展联学共建暨党建经验交流活动

2025/12/11

-

学习贯彻党的二十届四中全会精神,应用经济学院教授开讲!

2025/12/10

-

强国一代有我在!应用经济学院学子唱响《先锋·人大组歌》

2025/12/10